Chapter 2 Simple Linear Regression

\(\newcommand{\E}{\mathrm{E}}\) \(\newcommand{\Var}{\mathrm{Var}}\)

2.1 The Simple Linear Regression (SLR) Model

2.1.1 Goal of SL

In simple linear regression (SLR), our goal is to find the best-fitting straight line, commonly called the regression line, through a set of paired \((x, y)\) data. The line should go through the “middle” of the data and represent the “average” trend. Throughout this chapter and the next, we will look at how to more precisely define what the line represents, how to interpret it in context, and how to estimate it.

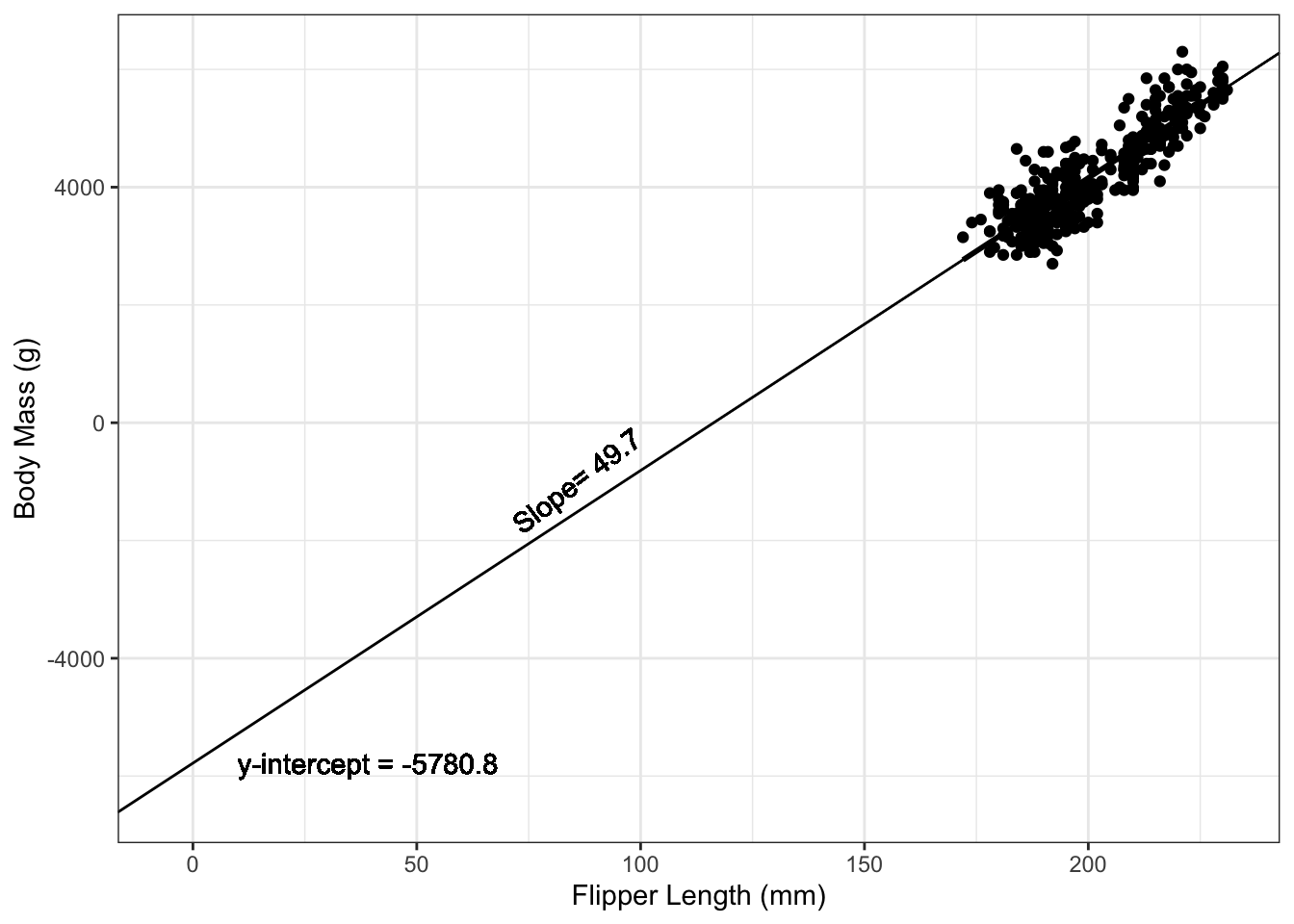

Example 2.1 In Example 1.1, we introduced data on penguin flipper length and body mass. We could seek the linear regression line for this data:

2.1.2 SLR model

The equation for the Simple Linear Regression (SLR) model is:

\[\begin{equation} Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1x_i + \epsilon_i \tag{2.1} \end{equation}\]

where:

\(Y_i\) is a random variable representing the outcome (e.g. body mass)

\(x_i\) is a fixed predictor variable (e.g., flipper length)

\(i\) is an index for each observation (penguins, people, units, etc.)

\(\beta_0\) is a parameter representing the intercept

\(\beta_1\) is a parameter representing the slope

\(\epsilon_i\) is a random variable representing variation (the “error” in the model)

These five elements can be categorized as three different kinds of quantities:

- Random variables (\(Y_i\) and \(\epsilon_i\)): Random quantities that are not directly observed. For a given dataset, the corresponding observed values will be denoted \(y_i\) and \(e_i\) (See Section 2.3)

- Parameters (\(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\)): Numbers that are fixed but unknown. These values are the same for all observations in the model. Estimating the values of these parameters (the topic of Section 3) is the basic task in “fitting” a regression model.

- Observed data (\(x_i\)): Values that are fixed and known. Each observation can have a different value of \(x_i\), or there could be as few as only two distinct values for \(x_i\). Even though these might vary between datasets, the SLR model considers them fixed. SLR refers specifically to settings where there is only one predictor variable. In Chapter 8 we will extend this to multiple predictor variables.

2.1.3 SLR Model Assumptions

The assumptions corresponding to the SLR model (equation (2.1)) are:

- \(\E[\epsilon_i] = 0\)

- The error terms have mean zero. This allows the \(\epsilon_i\) to account for variability above and below the line.

- \(\Var[\epsilon_i] = \sigma^2\)

- The error terms have constant variance. (If the variance was different for each observation, then \(\Var[\epsilon_i] = \sigma_i^2\).)

- \(\epsilon_i\) are uncorrelated

- Each observation gives you new information. This usually means that each observation is independent.

For now, the key assumption is \(E[\epsilon_i] = 0\). Importantly, we do not require an assumption about normality of the error term. We will re-visit these assumptions in detail, and discuss what happens when they are violated, in Chapter 12.

2.2 Parameter Interpretation

2.2.1 Regression Line Equation

A consequence of Assumption 1 (\(\E[\epsilon_i] = 0\)) is that the mean of \(Y_i\) is a straight line:

\[\begin{align} \E[Y_i] &= \E[\beta_0 + \beta_1x_i + \epsilon_i] \notag\\ &= \E[\beta_0 + \beta_1x_i] + \E[\epsilon_i]\notag\\ &= \beta_0 + \beta_1x_i + 0 \notag\\ &= \beta_0 + \beta_1x_i \tag{2.2} \end{align}\]

This allows us to interpret the parameters \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) in terms of the slope and intercept of the line.

2.2.2 Interpreting \(\beta_1\)

The \(\beta_1\) parameter represents the slope of the regression line. In other words, \(\beta_1\) is the difference in \(\E[Y_i]\) between observations that differ in \(x_i\) by one unit.

In almost any data analysis project, an important task is providing an interpretation of the model parameters. When describing the interpretation of \(\beta_1\), it is important to include these key elements:

- An interpretation of \(\beta_1\) as an estimated difference in the average value of the outcome variable

- For linear regression, “difference in average” is the same as “average difference”. You can use either phrase.

- In this section only, we are assuming that \(\beta_1\) is known. Starting in Section 3 we will introduce estimates of this parameter and start including “estimated” in interpretations.

- Specify that this is for a 1-unit difference in the predictor variable (x).

- Be cautious about referring to \(\beta_1\) as an “increase” or a “decrease”. Those words imply that an intervention was conducted, in which the value of \(x\) was directly modified. This is possible in controlled experiments, but is not the case for observational datasets. To indicate direction, it can be helpful to use words such as “greater”, “lower”, or “higher”.

- Include confidence intervals (see Section 4.8)2

- If appropriate, include information about the conclusion from a hypothesis test (see Section 4.5)3

- Include units for both the outcome and predictor

- If known, include statement about population/context.

Example 2.2 Consider two groups of penguins:

- Penguins that have flipper lengths of 201mm. Call this “Group A”

- Penguins that have flipper lengths of 200mm. Call this “Group B”

Assuming the SLR model (2.1), what is the difference in average body mass between these groups of penguins? To answer this, first write out the regression equation for the mean body mass in each group:

\[\text{Group A:} \quad \E[Y_A] = \beta_0 + \beta_1*201\] \[\text{Group B:} \quad \E[Y_B] = \beta_0 + \beta_1*200\]

Then take the difference between them: \[\begin{align*} \E[Y_A] - \E[Y_B] &= \left(\beta_0 + \beta_1*201 \right) - \left(\beta_0 + \beta_1*200\right)\\ & = 201\beta_1 - 200\beta_1\\ &= \beta_1 \end{align*}\]

Possible summarizing sentences for \(\beta_1\):

- \(\beta_1\) is the difference in average body mass (in g) for penguins that differ in flipper length by 1 mm.

- The average difference in body mass for penguins that have 1 mm longer flippers is \(\beta_1\) grams.

- The difference in average body mass for penguins that differ in flipper length by one millimeter is \(\beta_1\) grams.

We will expand upon these sentences in Examples 2.8 and 4.7.

2.2.3 Interpreting \(c\beta_1\)

Because \(\beta_1\) is the slope of the regression, we can easily interpret multiple of \(\beta_1\), say \(c\beta_1\) for some \(c \in \mathbb{R}\), as differences in the average value of the outcome variable for differences of \(c\) units in the predictor variable.

Example 2.3 In Example 2.2, the value \(10\beta_1\) can be summarized as: the difference in average body mass (in g) for penguins that differ in flipper length by 10 mm.

Example 2.4 In Example 2.2, the value \(25\beta_1\) can be summarized as: the difference in average body mass (in g) for penguins that differ in flipper length by 2.5 cm.

Interpreting multiples of \(\beta_1\) is closely related to the idea of re-scaling the predictor \(x\), which is covered in Section 7.2.

2.2.4 Interpreting \(\beta_0\)

The \(\beta_0\) parameter represents the intercept of the regression line. In other words, \(\beta_0\) is the average value of \(Y_i\) (i.e. \(\E[Y_i]\)) for observations with an \(x\) value of 0. While mathematically useful, \(\beta_0\) might make no practical or scientific sense!

When describing the interpretation of \(\beta_0\), follow all of the same guidelines as for \(\beta_1\) above, with the following exception:

- Interpret it as the average value of the outcome variable (as opposed to a difference in the average value).

- Specify it corresponds to a value of 0 for \(x\), rather than a 1-unit difference in \(x\).

Example 2.5 Consider a third group of penguins:

- Penguins with flipper length of 0 mm. Call this “Group C”

\[\text{Group C:} \quad \E[Y_C] = \beta_0 + \beta_1*0 = \beta_0\]

Equivalent interpretation statements for \(\beta_0\) in this context:

- \(\beta_0\) is the average body mass (in g) for penguins that have a flipper length of 0 mm.

- The average body mass for penguins that have 0 mm long flippers is \(\beta_0\) grams.

2.2.5 Interpreting \(\beta_0 + \beta_1x_i\)

From Equation (2.2), the points on the regression line can be interpreted as the average value of the outcome variable for units with a particular value of \(x\).

Example 2.6 Consider penguins in Group A (from Example 2.2). In terms of parameters in the simple linear regression mdoel, what is their average body mass?

Since penguins in Group A have flipper lengths of \(x_i = 200\)mm, their average body mass is given by:

\[\E[Y_i | x_i = 200] = \beta_0 + 200\beta_1.\]

In Section 5, we will see more on how to interpret this value and the difference between estimating a mean and predicting a new observation.

2.2.6 Interpretation of \(\sigma^2\)

The parameter \(\sigma^2\) represents the variance of the data around the regression line:

\[\begin{align*} \Var(Y_i) &= \Var(\beta_0 + \beta_1x_i + \epsilon_i)\\ &= \Var(\beta_0 + \beta_1x_i) + \Var(\epsilon_i)\\ &= 0 + \sigma^2\\ &= \sigma^2 \end{align*}\]

- A large value of \(\sigma^2\) means that data are more spread out vertically around the line.

- A small value of \(\sigma^2\) means that data are vertically close to the line

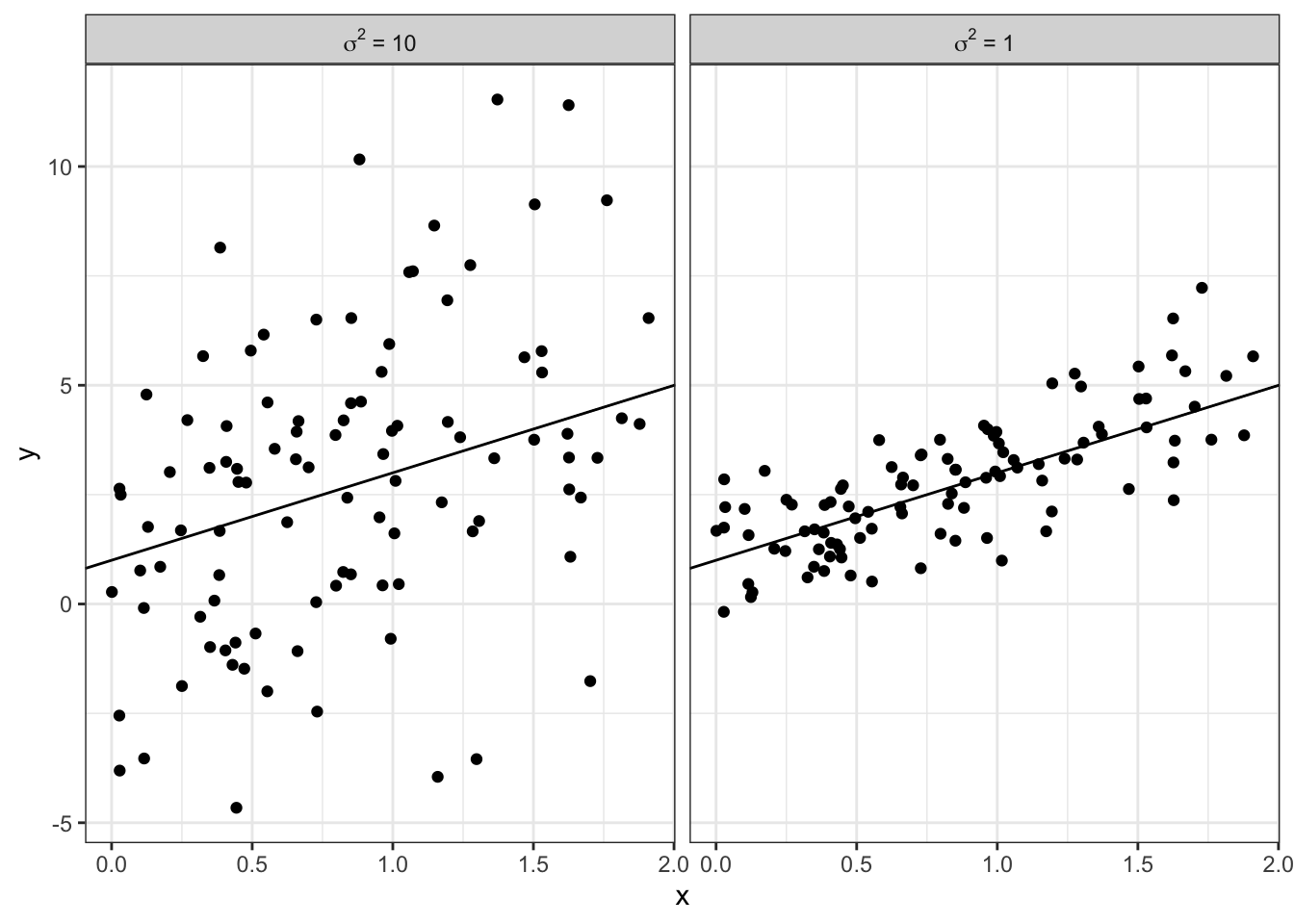

The following two plots show simulated data. The left panel has data generated from a model with \(\sigma^2 = 10\) and the right panel data comes from a model with \(\sigma^2 = 1\).

Figure 2.1: Simulated data showing the impact of different values of \(\sigma^2\).

2.2.7 Interpreting \(\beta_1\) with binary \(x\)

Although the most common setting of the simple linear regression model is with a continuous predictor variable (such as flipper length), the model can equally be applied when the predictor variable is binary, meaning it takes on two values.

If \(x_i\) can take on two values, then instead of a line, the SLR model simply becomes two distinct average values for the two groups. Suppose for one group, \(x = 0\) and for the other group, \(x=1\). A variable defined this was is called an indicator variable since it serves as a binary marker of group membership. The two groups could be anything, such as male/female, home/away, automatic/manual, etc. (We will see how to use indicators for variables with 3 or more categories in Section 11.)

Then the two “lines” for the model are: \[\begin{align*} \E[Y_i | x_i = 0] &= \beta_0 \E[Y_i | x_i = 1] &= \beta_0 + \beta_1*1 = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \end{align*}\] The average value of the outcome for those with \(x_i=0\) is \(\beta_0\) and the average value of the outcome for those with \(x_i =1\) is \(\beta_0 + \beta_1\). Furthermore, the difference between these values is: \[\begin{align*} \E[Y_i | x_i = 1] - \E[Y_i | x_i = 0] &= (\beta_0 + \beta_1) - (\beta_0) \\ &= \beta_1 \end{align*}\] Thus, the interpretations of \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) are:

- \(\beta_0\) is the average value of \(Y\) among observations in the group with \(x=0\)

- \(\beta_1\) is the difference in average value of \(Y\) between observations with \(x=1\) and those with \(x=0\).

Example 2.7 Consider the penguin data, but now when we model body mass (the outcome) as a function of penguin sex (the predictor variable). Define the indicator variable

\[\begin{equation} x = \begin{cases} x=0 & \text{ if } \texttt{sex} \text{ is } \texttt{"female"} \\ x=1 & \text{ if } \texttt{sex} \text{ is } \texttt{"male"} \end{cases}. \tag{2.3} \end{equation}\] Then in the SLR model \(Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1x_i + \epsilon_i\), we have the following interpretations for the regression parameters:

- \(\beta_0\) is the average body mass for female penguins.

- \(\beta_0 + \beta_1\) is the average body mass for male penguins.

- \(\beta_1\) is the difference in body mass between male and female penguins.

2.3 Random Variables v. Data

The SLR model (2.1) is an equation for the line for theoretical random variables \(Y_i\). In practice, we observed data \(y_i\) and estimate a line that has an estimated slope and intercept.

In other words, real data are not generated from the theoretical model \[Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1x_i + \epsilon_i\] But for a dataset with specific values \((x_i, y_i)\), we can use the theoretical model to describe the data:

\[\begin{equation} y_i = \hat\beta_0 + \hat\beta_1x_i + e_i \tag{2.4} \end{equation}\]

In equation (2.4):

- \(y_i\) is the observed value of the outcome for observation \(i\)

- \(e_i\) is the residual value corresponding to observation \(i\)

- \(\hat\beta_0\) is the estimated intercept for the regression line

- \(\hat\beta_1\) is the estimated slope for the regression line

- \(x_i\) is observed value of the predictor variable for observation \(i\)

The “hats” in \(\hat\beta_0\) and \(\hat\beta_1\) indicate that the values are estimates of the true parameter \(\beta_1\) and \(\beta_0\). The difference between the theoretical model and estimated model can be summarized in the following table:

| Theoretical/Math World | Real World Data |

|---|---|

| \(Y_i =\) outcome (a random variable) | \(y_i =\) outcome (a known number) |

| \(x_i =\) predictor (a known number) | \(x_i =\) predictor (a known number) |

| \(\epsilon_i=\) error (a random variable) | \(e_i =\) residual (a known number) |

| \(\beta_0 =\) intercept parameter (an unknown number) | \(\hat\beta_0 =\) intercept estimate (a calculated number) |

| \(\beta_1 =\) slope parameter (an unknown number) | \(\hat\beta_1 =\) slope estimate (a calculated number) |

| \(\sigma^2 =\) variance parameter (an unknown number) | \(\hat\sigma^2 =\) variance estimate (a calculated number) |

2.4 Putting it together: Penguin example

Example 2.8 In the example of penguin flipper length and body mass, the equation for the estimated regression line is: \[y_i = -5780.8 + 49.7*x_i\] (We will see how these numbers are calculated in Section 3.) We can interpret the slope of this regression line as follows:

A difference of one mm in flipper length is associated with an estimated difference of 49.7 g greater average body mass among penguins in Antarctica.

Note the key elements in this sentence:

- “average” – Linear regression model tells us about the mean, not a specific observation

- “estimated” – The number 49.7 is an estimate of the true (and unknown) parameter value.

- Units are provided for flipper length and body mass.

- “among penguins in Antarctica” – Context and/or population

- This is observational data, so the relationship is stated as an association, not causation.

Figure 2.2: Fitted regression line for penguin data.

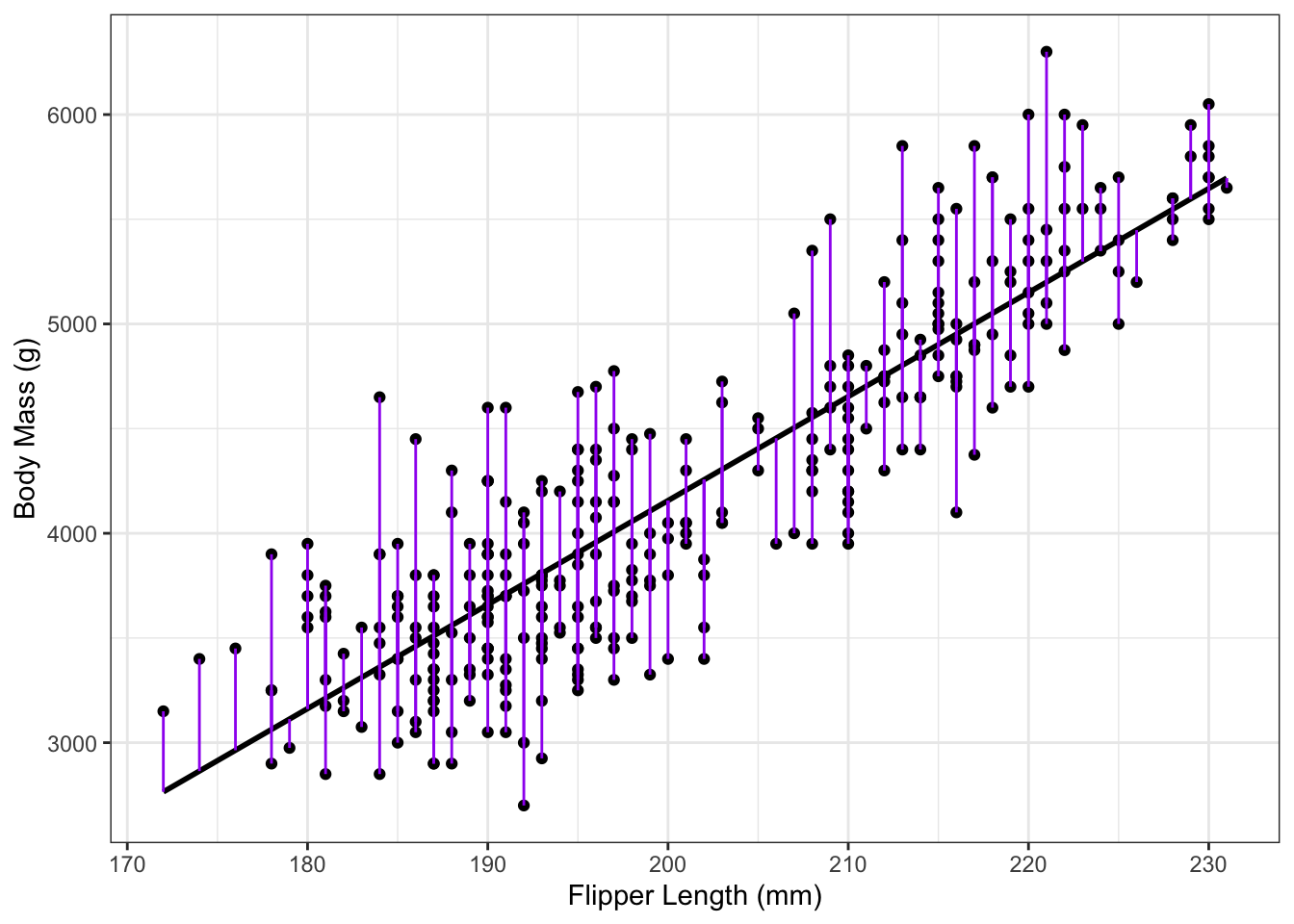

The residuals for each observation can be calculated as the difference between each data point and its corresponding modeled mean: \[ e_i = y_i - (\hat\beta_0 + \hat\beta_1x_i)\] Figure 2.3 shows a graphical representation of the residuals \(e_i\).

Figure 2.3: Residuals for penguin data.

2.5 Exercises

Exercise 2.1 In the context of Example 2.2, what is an interpretation of \(5\beta_1\)?

Exercise 2.2 In the context of Example 2.5, does the quantity \(10\beta_0\) make practical sense? If yes, provide an interpretation. If no, explain why not.

Exercise 2.3 Consider a variation of Example 2.2, in which a simple linear regression mdoel is fit with body mass (in g) as the predictor variable and flipper length (in mm) as the outcome. Explain how this switch affects the interpretations of \(\beta_0\), \(\beta_1\), and \(\sigma^2\).

Exercise 2.4 Consider a SLR model with flipper length as the outcome and sex as the predictor, with \(x\) defined as in equation (2.3). What are the interpetations of \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\)?

Exercise 2.5 In the SLR model of Example 2.7, what is the difference in average body mass between females and male? (Note that the order of the queston is important here).